The MTA Promises to Make Subways 95% Accessible: Is Their Plan Enough?

Introduction

Many New Yorkers are able to travel like clockwork, muscle memory swiping their card and pushing themselves through the turnstiles, climbing the stairs to a platform and waiting for the train to rush into the station. Listening to the robotic voice call out to “Stand Clear of the Closing Doors Please.” Or simply waiting for the bus and hopping on when it pulls in at their stop. Straightforward, effortless, easy. However, for some people, public transportation, especially the subway system is less a mediocre part of a daily routine and more akin to a labyrinth. Transportation in New York City can be a complication for people with disabilities, the elderly and those with strollers and small children, as most stations are not equipped with accessible architecture. The New York City subway system is built for fast paced, able bodied pedestrians, not for those who have mobility issues or use a wheelchair. In June, a lawsuit was settled between the MTA and Disability Rights Advocates (DRA) which required subway stations to be made 95 percent accessible, mostly through building new elevators. While the MTAs plan to build new elevators in the New York City subway stations will make traveling by train significantly more accessible, it is not a permanent solution to the issues disabled New Yorkers face when commuting, and is just the beginning of improving the accessibility of NYCs public transportation. Further improvements can be made to both the MTAs plan for increasing accessibility in the subways, and to city buses in order to ensure that all New Yorkers have access to low cost and convenient methods of transportation.

Disabled Commuters Face Difficulties Traveling

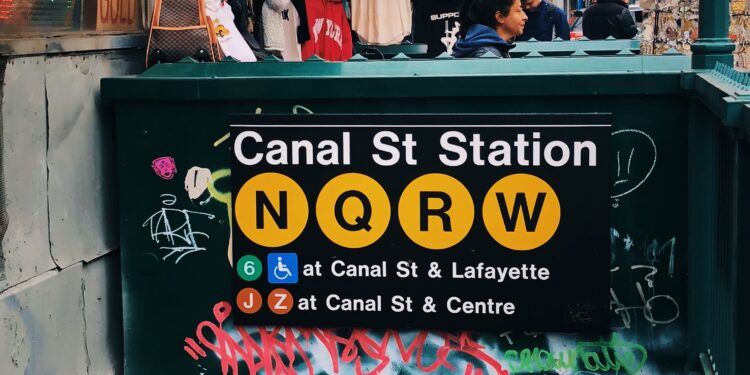

While transit systems in other parts of the country such as Washington, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Chicago and Boston are very, if not 100 percent, accessible, New York falls far behind with only about 27 percent of stations being usable for people with disabilities. As the subway is one of the cheapest and fastest forms of transportation in the city, it is one many people, including disabled people, turn to in order to travel. Yet, they are forced to turn to slower or more expensive ways to get around when the lack of accessibility in a station fails them. These people all have places to be, school, their jobs, and not having access to fast transportation can make it difficult to get where they need to be and to simply function and live their lives. 29% of people with disabilities in New York are currently unemployed, and a lack of affordable public transportation is a leading cause in this number. Janno Lieber, the transit authorities chairman spoke up about this issue, stating that, “We don’t have equity, we don’t have equality, if people are left out of their ability to use a mass transit system that for so many people — more than half of New Yorkers — is the only way to get around.”

Those who can continue to use the subway, even at stations where elevators and ramps are not available, will navigate the stairs. However, this is both time consuming and dangerous, causing people to miss their trains. Samuel Jimenez, who is 65 and uses a cane, lives near the Montrose station in Brooklyn, which does not have an elevator. Because of this, he has to go down the steps at his station which takes him, “an hour and a day.” He says that, “it slows me down quite a bit. I miss a lot of trains because of that.” Even at the stations that do have elevators, many are poorly maintained, unclean and frequently out of service, which intensifies the issue.

The MTAs Plan For Accessibility in NYC Subway Stations

The fight for accessibility in the New York Subway system has been going on for many years. In 2017, a lawsuit was filed against the transit system by a group of disabled residents and organizations. They claimed that the MTA had violated New York’s Human Rights Law, which prohibits discrimination on behalf of factors such as race, age, gender, dissabilities, sexual orientation and much more, through not providing enough elavators in the subways for those who need them.

In 2019, another lawsuit was filed accusing the MTA of acting in violation of the Americans With Disabilities Act: an act passed in the 1990s which required public facilities to be accessible, when subway stations were renovated without inclusive technology and architecture such as elevators and ramps. As the court debate for this lawsuit reached its conclusion, it was announced that officials had approved a 5.2 billion dollar plan to equip 346 New York Subway stations with elevators by 2055. This expensive and laborious plan will allow thousands of disabled people to travel in the subways freely without having to worry about if a station they get off or on at will have an elevator, or having to find an alternate way to travel, but is this progress enough?

Is it enough?

Short answer: not quite. While this plan will drastically improve subway accessibility for disabled commuters, there are still steps that will need to be taken to make the subways fully accessible. At the end of the day, elevators are pieces of machinery which can break down or need repairs, and while signs are put up if it’s been broken for a day or two, the transit system has no way of notifying passengers beforehand if elevators are broken. Monica Bartley, a wheelchair user and community outreach specialist, advocates for change, says, “we want the MTA to post a schedule for maintaining elevators. We’d like to see improvements on the maintenance of elevators because too many of them are broken during the course of the day. They do not inform us in real time about broken elevators. And so, it is really frustrating when we get there and realize that the elevator is broken.” In response to this issue, updates should be posted on the NYC Subway’s app, which many commuters use to see when their train is arriving, so that there will be less complications and they can try and find a different route, without going to a station just to realize they cant use an elevator to transfer to a different train or get off at their stop.

Furthermore, most if not all stations and subway cars are equipped with maps of the subway and the different lines within it. All stations should have one of these maps, which should be updated to include a symbol over stations that indicates which ones are currently accessible.

And lastly, the newly announced plan entails nothing about including wide turnstyles within renovations. Wide turnstyles have been an experimental design included at 5 subway stations, which are essentially turnstyles made to accommodate people in wheelchairs, with walkers or strollers. Incorporating this new turnstyle design into more stations would allow people to enter stations more smoothly and quickly, and without having to rely on someone else to open the door for them.

Commuting During the Wait

Despite the fact that this plan is a significant change, it is set out to be an extremely slow one, as sadly it will be 33 years before the transit system is accessible. Even then, it will not be completely, but 95 percent accessible. After 5 years of lawsuits, a fully accessible subway will not come for decades. “We would like sooner. But they say they can’t do it sooner. And you can’t make somebody promise to do something they can’t do” says Jean Ryan, who is the President of the organization Disabled in Action, which acted as a plaintiff within the lawsuits.

Understandably, renovating a subway station is not quick work, and to do this to over 300 stations is a momentous task. But it does raise the question: if the subways cannot be fully accessible till 2055, what forms of public transit can be more easily made more accessible for New Yorkers in the meantime? While dissabled commuters have access to services such as Paratransit whose drivers are experienced at helping people get in and out of a vehicle, at 5 dollars the fair is almost double that of the subways and those who want a ride have to book it ahead of time, they can’t just wait at a stop and hop on, which can be inconvenient. Of course, there are city buses, where passengers can just wait for a bus and get on: all of which are equipped with wheelchair lifts. However, due to the backlog of traffic and the sluggish mileage of buses, taking the bus can be very slow and unfavorable for commuters who are traveling longer distances.

Luckily, changes are being made to the bus system, changes that will come about much faster than the ones happening to the subway system. On June 16th, Mayor Eric Adams announced plans to build 150 miles of bus routes over the next four years, which he says will start off with, “20 miles of bus lanes in 2022 that will increase daily ridership to approximately 327,000 New Yorkers.” This plan hopes to bring about a faster and more reliable bus system, which all commuters can benefit from, especially those who cannot access the subways.

Improving the Accessibility of City Buses

Yet, simply having more bus lanes will not solve the issues many dissabled people face when riding the bus. While all city buses are equipped with wheelchair lifts, many of the bus drivers are underprepared to operate these lifts. “All of the other passengers besides me, but including me, as well as the passengers who are waiting on different stops…they’re all impacted when it takes the bus driver 15 minutes to get me on. Until they solve this problem, the buses are going to continue to be slow.” Said Jean Ryan in response to the issue. City Bus drivers should be properly trained to learn how to operate the lifts and be prepared to have dissabled passengers on board. While Eric Adams claims that the city buses will become faster and more accessible in the next few years, having bus drivers take 20 minutes just to help to get someone with a wheelchair onto a bus is sure to hinder this plan and is an inconvenience for everyone. Additionally, many of the buses have older models of wheelchair lifts that require the bus driver to go outside the bus to open it, which are more complicated and time consuming, and should be replaced with newer flip out models.

Conclusion

After decades of violations of inclusive acts, New York City has begun the slow crawl to develop the subways so that citizens and future generations will have more accessible transportation. Although these changes will have met the requirements of the 2019 lawsuit and are a massive step forward, it is important to remember that accessibility extends far beyond implementing elevators in the subways and should be extended to other methods of transportation as well. This lawsuit serves as a reminder to the city and its officials that public spaces should be made available to all.